What is memory and how it affects learning

The influence of memory on study

Many students believe that their memory is like a library, that once something is learned, that knowledge is banked and there is no need to revisit it. The library metaphor also means that students expect that retrieving knowledge should be easy, just like taking a book down from the shelf.

Unfortunately, both beliefs are incorrect, and they actually disempower students when it comes to effective learning. When students learn how memory truly works, they are better informed to study and learn in ways that work with, instead of against, their brains.

Learning is a life skill

Learning is not only necessary at school, but also for life more broadly. Sports are far more technical than they used to be, hobbies have steeper learning curves and more facets and components. Throughout their careers, people are also required to learn more, at a faster pace, and retain knowledge for longer periods given the increasingly complex nature of work.

The more that students can learn about how to effectively learn and remember information, the more they are prepared to face learning and memory challenges during their schooling, and beyond the school gates.

What do the experts say?

There are two main ideas that students need to know when it comes to memory; the first is about how memory is structured, and the second is about how forgetting happens (and how to overcome it!).

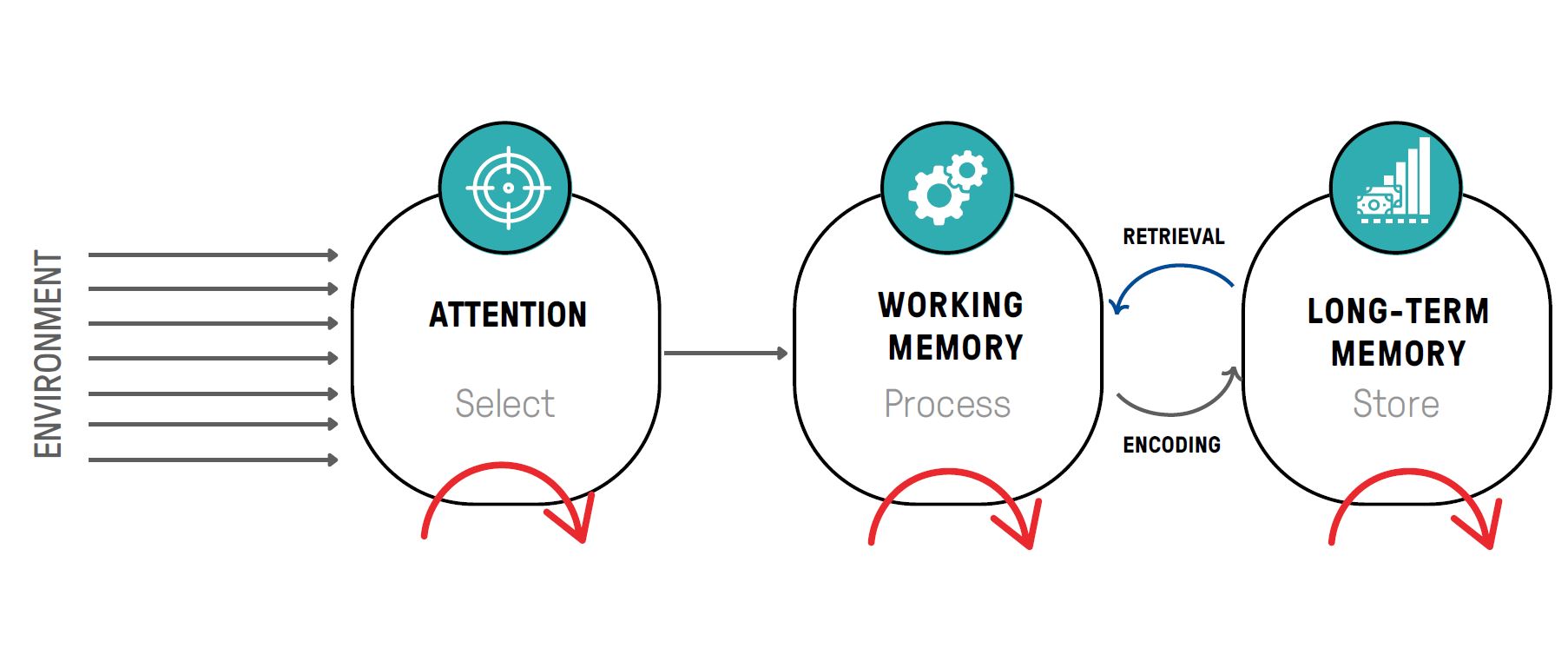

The human memory system is made up of three key components; the environment, working memory, and long-term memory (Willingham, 2009).

The environment is the external world, it’s where textbooks, teachers, classmates, and Google live. The environment is where new information comes that can be learned. When students pay attention to information in the environment, this attention brings that information into their working memory.

Working memory is the place where we do our thinking. Whenever we plan what we’re going to say, ponder an idea, or make a plan, this all happens in our working memory.

Unlike the environment, our working memory is limited, it can only hold about seven items of information at any one time (Miller, 1956). In this way, thinking is like juggling. We can only juggle a limited number of balls at a time, and it takes concentration and focus to do so. When we do focus on new information effectively and connect it to what we already know, we can learn it, and it begins to become embedded in our long-term memories.

For your child, this means that attention is a vital part of learning. During class, it is essential that students are engaged in listening to the explanations of the teacher and are thinking deeply about the content. Learners need to then link this new knowledge to skills they learned last lesson and last week. Through our Effective Learner teaching model, teachers check for understanding through short activities (answer a question, write a sentence). This is a powerful process for maximising learning.

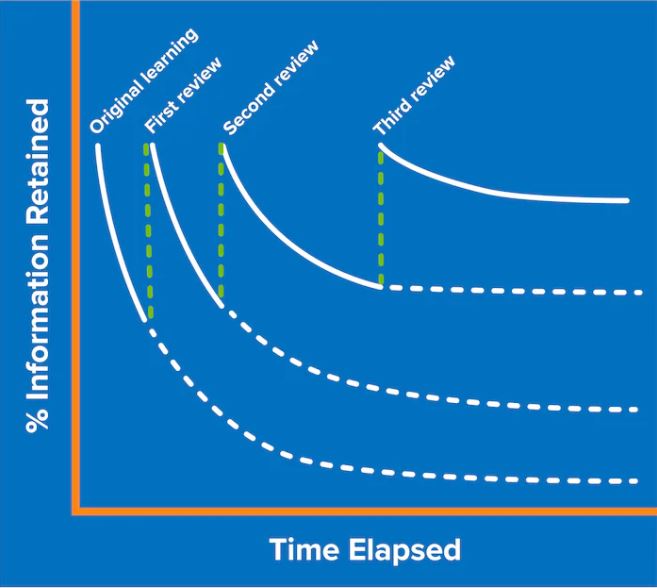

However, once something is learned and stored in our long-term memories that idea isn’t static. It’s often quite fragile, and the neural pathways representing that memory will degrade over time unless we reactivate them (Ebbinghaus, 1885; Wozniak & Gorzelanczyk, 1994).

We all forget based on a forgetting curve. If we don’t revise information, we slowly forget it more and more (as in the white line below). If we do revise it regularly over time, our memories grow stronger (green lines below), and we forget more slowly after each retrieval.

Learning and memory

In the school context, we take account of both the structure of memory and the nature of forgetting, to maximise students’ learning.

The important takeaway from the model of the human memory system described previously is that working memory is limited. When we are thinking hard, we are performing a mental juggling act. There are two main ways that a juggling act can be undermined. Firstly, the juggler can try to juggle too many balls, and secondly, they can get distracted.

Within classrooms, we can ensure that we don’t ask our students to juggle too many balls at a time by ensuring that we provide them with instruction in small steps, and provide opportunities for students to practise after each step (Rosenshine, 2012).

Schools should ensure that students don’t get distracted and drop the ball, by working hard to build a focused, academic culture within the classroom. A culture in which every student contributes to a calm and focused learning environment. Each student has an important role to play in building this culture within the school.

To combat forgetfulness, schools should provide structured opportunities for students to revisit key ideas within all subjects, often in the form of starters or a do now at the very beginning of each lesson (Lemov, 2010). These types of carefully designed activities are crucial opportunities for students to reactivate their memory pathways and refine them which will consolidate their learning for the long term.

How can you help?

- Ensure that your child’s study environment is free from distractions (TV, Netflix, phones, etc).

- Encourage the importance of paying attention during explanations when learning new concepts.

- Support your child to focus on learning whilst they are studying and congratulate them for achieving increasingly long intervals of focused attention and work.

- Encourage your child to regularly revisit key ideas, and to spread this learning out over time. A good way to do this is to have them explain to you some ideas and concepts from prior topics and terms.

- Model focused and sustained attention in your own work with a distraction-free working environment and by demonstrating deep work and focus for extended periods.

Resources

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Über das gedächtnis: untersuchungen zur experimentellen psychologie. Duncker & Humblot.

Evidence Based Education (2020,11,27) Science of Learning, https://evidence-based-education.thinkific.com/courses/resource-library.

Lemov, D. (2010). Teach like a champion: 49 techniques that put students on the path to college (K-12). John Wiley & Sons.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological reviewReview, 63(2), 81

Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American educator, 36(1), 12.

Schimanke, F., Mertens, R., Vornberger, O., & Hillebrand, J. (2016, November). Enhancing Mobile Learning Games with Spaced-Repetition and Content-Selection Algorithms. In E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education (pp. 1270-1279). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE)

Willingham, D. T. (2021). Why don’t students like school?: A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. John Wiley & Sons.

Wozniak, P. A., & Gorzelanczyk, E. J. (1994). Optimization of repetition spacing in the practice of learning. Acta neurobiologiae experimentalis, 54, 59-59

Resources

Can prior knowledge increase task complexity?

Cases in which higher prior knowledge leads to higher intrinsic cognitive load

Do you want to be part of our Staff Development Network?

Sign up to receive our newsletter